It is always difficult to know how to provide value on a post like this, because the church has been so thoroughly covered elsewhere (for example Stephen Humphrey's book

). But it is impossible to maintain a blog that centres so firmly on Rotherhithe's past without talking about the church, because St Mary's Rotherhithe, maintaining a thriving congregation even today, has been central to the Rotherhithe village community for 300 years. 2015 is its tercentenary, a very special anniversary for a very special church. So here's a short history of the church, and to celebrate its role in the community I have added special references to the maritime and river world that the church served, setting it in the context of its changing local social and economic background and highlighting one or two individuals of note who were connected with St Mary's.

I have added a list of the main sources of information for this post at the end, with my thanks. Unless otherwise stated, all the hyperlinks in this piece link to earlier posts on this blog, which contain more relevant information. Unless otherwise stated, photographs by Andie Byrnes.

St Mary's Rotherhithe is a Grade II* Listed Building located in the heart of Rotherhithe village, the

oldest settlement area of Rotherhithe peninsula, and arguably the most

attractive. Referred to locally as St Mary's Rotherhithe, the full name of the church is St Mary the

Virgin. The church sits on St Marychurch Street today, but this name was

only given to the road in 1892, before which it was Church Street, and

before that Church Lane. There has been a church here since the 12th Century.

Like all churches, its external architecture has not remained static, and its interior has undergone substantial changes. It has been added to and altered many times, a product of the changes in the community that surrounds it and different needs at different periods of its history. It is located next to one of Rotherhithe's oldest buildings, an 18th Century house that became a school in 1742 but was probably built in the early 1700s. These two lovely 18th Century buildings are surrounded by 19th Century buildings of all

sizes and job descriptions. The church's former overflow churchyard is now a

small park, but the churchyard immediately surrounding St Mary's is partly preserved.

|

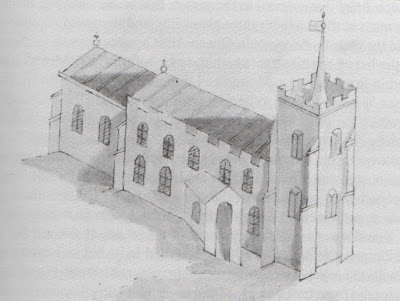

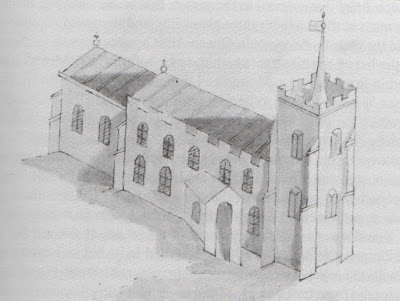

St Mary's in 1623, by Samuel Palmer. Taken from "The Story of

Rotherhithe" by Stephen Humphrey (1997, p.9) |

Rumour has it that the first church was built on the remains of a much earlier structure, and included Roman

building material. A church was certainly here during the reign of Edward I the late 13th Century, when it was under the jurisdiction of Bermondsey Abbey, and parish records for the church date back to the 1500s. Between 1537 and 1562 its rector, John Fayrwall, apparently managed to maintain his role at the church during the Reformation. There is only one image that exists of the church that pre-dated the 1714-15

rebuild, and this was clearly a church that had itself been modified

many times during its lifetime. Drawn by Samuel Parsons and dating to

1623, it shows a nave with two tiers of windows, a northern porch, and a small eastern chancel. Buttress set-offs are shown all around the building. The 15th century tower at the west had a crenelated parapet, and a short needle spire. A splendid monument to Captain Anthony Wood, who died in 1625, was moved into the 1715 church and tells something of the early

17th Century shipping character of Rotherhithe. It shows a ship in

full sail, in high relief, with a commemorative text beneath it - see the photograph below. Although the church underwent

repair in 1687 it was in very poor condition.

|

| The memorial to Captain Anthony Wood |

During the 17th Century Rotherhithe's marshy and stream-incised interior

was not suitable for habitation and could be used for little more than pasture. All the activity in Rotherhithe at that time took place along the edges of the Thames. The riverside was

beginning develop east from central London, and Rotherhithe already had a

ship building industry at this time. The earliest known ship to be

built in Rotherhithe

was the 1654 HMS Taunton, commissioned by the Royal Navy for use

in the First Dutch War. The maritime wars of the 17th and early 18th centuries were the source

of a considerable amount of income for private ship builders and

repairers, and the river Thames was, of course, a vital artery for trade

throughout the 17th century. The residents

of Rotherhithe at this time would all have been involved in trades involving the river and the sea, both commercial and military. It was also a period of religious diversity. From the same era as the above-mentioned monument to Captain Anthony Wood, a group of post-Reformation religious dissenters known as

the Pilgrim Fathers sailed in the

Mayflower from the Thames at Rotherhithe in

1621, and the captain and part-owner of their ship, Captain Christopher Jones, was a local man. He died on the 5th March in 1622, in his early 50s, and was buried in the churchyard of St Mary's in Rotherhithe. During the 1705 flood and the 1714-15 reconstruction of the church many of the old churchyard monuments and memorials were lost, and the exact location of the burial of Christopher Jones is no longer known. There is modern monument to him in the churchyard of St Mary's, depicting St Christopher, the patron saint of travellers, holding a small child. It was unveiled in 1995, to mark the 375th anniversary of the voyage. Two other Rotherhithe residents, John Moore and John Clarke, were included in the crew. John Clarke was the First Mate of the Mayflower. He was baptized at St Mary in 1575, so he was almost certainly born in Rotherhithe, and he died in 1622. Clarke Island in Plymouth Bay, Massachusetts, is named after him.

Another contemporary of the old church was Peter Hills, whose legacy

founded the charity school for the children of impoverished seamen in the immediate vicinity of St Mary's. Peter Hills died on 26th February

1614, a century before the new St Mary's was built in 1714-15.

Fortunately, some of the memorials were taken from the old church and

installed in the new one, and the Reverend Beck, writing in 1907, tells

how the three portions of a monumental brass dedicated to Peter Hills

and embedded into the floor of the old church were taken into the new

church and, because they were so badly eroded, were mounted on wood and

hung on the wall. The brass includes a portrait of Peter Hills and both

wives and the inscription reads:

Here

lies buried the body of Peter Hill, Mariner, one of the eldest Brothers

and Assistants of the Company of the Trinity, and his two wives; who

while hee lived in this place, gave liberally to the poore, and spent

bountifully in his house; and after many great troubles, being of the

age of 80 yeeres and upward departed this life without issue, upon the

26 February, 1614.

This was made at the charge of Robert Bell.

Though Hills be dead,

Hills' Will and Act survives

His Free-Schoole, and

his Pension for the Poore;

Thought on by him,

Performed by his Heire,

For eight poore Sea-mens

Children, and no more

|

The Blome Map of 1673 showing the spread of

industry and habitation along the Rotherhithe riverside |

By the late 17th Century the medieval church had fallen into serious disrepair, partly due to repeated flood damage throughout the decades that had not only destroyed furnishings but had seriously undermined the structural foundations. The river had been recorded breaking its banks in Rotherhithe throughout St Mary's long history, and in 1705 it did so again, flooding both the church

and the graveyard. The churchyard had housed a bone house, but this and the bones it contained were destroyed by the floods, and the site was unconsecrated so was not used for burials.

A church was vital to the community, its natural core, so plans were made to replace the existing church with a new one. There was great hope in the local community that they would be able to benefit from the Fifty Churches Act, a government-inspired initiative to create more places of worship in London, funded by a tax on coal. The argument outlined in the petition put forward by Rotherhithe residents was persuasive. They attempted to convince the Commission that the community's multiple roles in bringing the coal that was being levied for the building programmes should qualify them for the a new church "being chiefly seamen and Watermen who venture their lives in fetching those coals from Newcastle which pay for the Rebuilding of the Churches in London and the Parts adjacent." However, the bid for this funding was unsuccessful and the community had to pull together to raise the funds for the new church themselves. Funding came from both voluntary contributions and the money that was charged for burials. By 1714 they had raised

£4000 (which the National Archives Currency Converter estimates at £306,360.00 in today's money), which was sufficient to purchase a 1000 people capacity church, although financial difficulties were ongoing for many years afterwards and they had to defer plans to build a new tower. The architect John James was appointed and it was he who established the essential ingredients of the architecture that we see today.

|

St Mary's Rotherhithe in the with its 1747 tower, with ships in the

background and a rather untidy churchyard in the foreground.

From Beck 1907. |

John James is generally considered to have been a competent but unremarkable architect. Although he built several residential and commercial buildings, and submitted a design for Westminster Bridge, his main income was derived from work on churches. He had worked for Sir Christopher Wren during the construction of St Paul's Cathedral, collaborated with Nicholas Hawksmoor on the construction of two London churches, one of which was in Southwark and, somewhat ironically, served as a surveyor for the Commissioners for the Building of Fifty New Churches. Many of his churches featured tall arched windows, similar to those at St Mary's Rotherhithe. John James is best known for the church of St. George's Hanover Square, London, a very different architectural conception from that of St Mary's.

|

One of the more attractive of

the gravestones in the churchyard |

In many ways the 1714-15 church of St Mary's Rotherhithe is a typical 18th Century building, with its simple rectangular plan, its

clean lines and its distinctive arched and segmental-headed windows arranged

over two tiers. It is reminiscent of the style of Sir Christopher Wren,

whose influence on post Great Fire

London can be seen in many buildings in which he himself did not have a

direct hand. John James built the church mainly in yellow brick, which was attractive and cost effective (

and was used to build much of Rotherhithe's buildings) with decorative red brick used as dressing around windows and doors, only using the much more expensive stone elements for quoins (corner stones), window trim and other special features. The structure consisted of a nave flanked by internal aisles, a vestry and a sanctuary, but no chancel. James retained the 15th Century tower as shown in the Samuel Parsons illustration above, the remains of which can be seen in the vaults today. The church was provided with a burial ground, which surrounded it. Some of the gravestones and tombs are still dotted around, but others have been removed.

The skills of local ship builders were employed in the construction of the interior fittings for the church, and the four internal Ionic columns were made of oak ships' masts, which were then plastered and painted white. Originally the interior contained galleries, box pews and an elaborate three-tiered pulpit. The ceiling was provided with a central barrel vault. Although the carvings have been ascribed to Grinling Gibbons in the past, it is more likely that Joseph Wade

may have been responsible for many of the more elaborate wooden carvings in the church, as well as the original reredos. A monument to Joseph Wade is still hanging in the church, reading "King's Carver in his Majesty's yards at Deptford and Woolwich," which was erected on the south wall after his death in 1743.

See the British Listed Buildings website for the full technical description of the church.

|

The interior of St Mary's, showing two of the

Ionic pillars that were formed by masts

covered with a thin layer of plaster, and

mounted on pedestals. |

18th Century Rotherhithe was increasingly busy and its increasingly industrial fate was partly determined by the building of

the Howland Great Wet Dock in east Rotherhithe in the early 1700s. It was probably the

largest dock in Europe at the time (about half the size of Greenland Dock, which is built on top of the site), and attracted ship repair yards as well as new ship building docks. Between maritime commerce, the Royal Navy and the Great Dock, 18th Century Rotherhithe became an important base for people employed in maritime roles, from the lowliest rope-makers to the most prestigious ship builders. In the 1720s Mayflower Street was an elegant road of wonderful sea captain's

homes. Tragically, these are long gone. At the other end of the social scale were less salubrious properties. In 1722 Daniel Defoe encountered Redriff in his tour through Great

Britain: "We see several villages,

formerly standing, as it were, in the country, and at a great distance,

now joined to the streets by continued buildings, and more making haste

to meet in the manner; for example, Deptford, this town that was

formerly reckoned, at least two miles off from Redriff, and that over

the marshes too, a place unlikely ever to be inhabited; and yet now, by

the increase of buildings in that down itself, and the many streets

erected at Redriff, and by the docks and building-yards on the

riverside, which stand between both, the town of Deptford, and the

streets of Redriff, or Rotherhithe (as they write it) are effectually

joined." As Defoe describes, the interior of Rotherhithe was still quite marshy, and poorly drained, but a series of market gardens grew up, and the land became a mosaic of small plots turned over to all manner of horticulture. Industry, river commerce and housing were all still concentrated around the edges of the land, along the Thames foreshore where every form of industry and commercial activity associated with the river took place, the most prestigious of which was ship building. The most illustrious of the ship building enterprises were engaged in work

for the Royal Navy and the Honourable East India Company. The best known of the

Rotherhithe shipyards was Nelson Dock, now part of the Hilton Hotel complex.

The adjacent Nelson House, which stands today and is quite lovely, was

the ship builders house, and was built in the 1730s. By the end of the 1700s Rotherhithe was beginning to develop along far more elaborate lines, with many more homes, commercial enterprises and docks.

In 1730 an administrative change led to a strong link between St Mary's Rotherhithe and Clare College, Cambridge. Clare College purchased the advowson of the church, which meant that they now had the right to appoint new rectors to the church. Advowsons usually belonged to Manors, enabling the local Lord of the Manor to influence the rector and the church's role in the parish, but they could be bought and sold, and the benefit to them for Clare was that it allowed them to place their own Anglican clergy beneficially, securing a position for the individual and allowing Clare to influence policy. The first to be appointed was Thomas Curling in 1734.

|

The Barrow Memorial

1775 |

The 16th Century church tower did not survive the 18th century and the decision was made

to replace the current tower and steeple in the 1730s, but this was not

completed until 1747. The job of building the new three-storey new tower was given to the

improbably-named architect Lancelot Dowbiggin. It was probably built to the original designs provided by John James, which could not be completed at that time due to funding problems. The tower was completely

consistent with the rest of the building, in yellow and red brick with

stone facing and arched windows. Its parapet at the top of the tower

features a modillion cornice. The tower was furnished with clocks on three faces, a steeple (composed of a louvred belfry with Corinthian columns, a lantern and small spire). The new tower is shown above as it appeared in the late 1700s, and of course survives today.

The

organ was created by John Byfield Senior in 1764-5, and although it has

been restored some of the original pipes and its original case survives,

decorated with musical instruments and trumpet-playing angels.

The first organist was Michael Topping who was paid £30.00 per year for

his services. Years ago I stumbled across a vinyl L.P. of music recorded on the St Mary's organ and it has a beautiful resonance. A decade later in 1775 another memorial was added. Captain Thomas Barrow dedicated the memorial to his wife Elizabeth who died at the age of 62. His own name was added to the memorial in 1789 when he himself died at the age of 72. The monument is an impressive one, with a coat of arms over the dedication and various funerary symbols surrounding it. The urn is a common funerary device on tombstones and mausoleums. There's a short but interesting

article on the Hand Eye Foot Brain blog about the contested origins of that motif.

|

St Mary's Rotherhithe and Rotherhithe village

in 1799 (the Horwood Map, copyright

www.motco.com) |

It was only at the

very end of the 1700s that ambitious plans for the development of new

docks in Rotherhithe were made. In 1796 the surveyor Charles Cracklow

proposed a new dock system, and William Vaughan, Director of Royal

Exchange Assurance Corporation (founded in 1720) and spokesman for the

West India Merchants, identified Rotherhithe, Wapping and the Isle of

Dogs as suitable riverside sites for potential expansion of dockland

areas. The new docks were proposed in order to meet the challenge of

London's ambitions to become a global centre for trade. The following

dockland developments were staggering, with architects and engineers

hired to plan and build new docks in the late 1700s, many of which

opened in the first years of the 1800s. Inland Rotherhithe in 1801 was rural, a series of marshes, streams and

fields. However, the Thames banks were lined with shipyards where

ships, barges and lighters were built and repaired. Rotherhithe's most

prominent ship builders were producing vast wooden vessels for the Royal

Navy and the East India Company. The only incursion inland was

Greenland Dock which had been established on the east side of

Rotherhithe in 1699. However in 1801 plans were rolled out to build the

Grand Surrey Canal, and in 1807 this opened and reached to the Old Kent Road

before being extended later to Camberwell and Peckham. The map of 1811 shows it as a conventional canal passing from Surrey

Basin across a nearly empty Rotherhithe, but a 1843 map shows

the extent to which the canal had been widened at this time, being

renamed the Inner Dock, whilst the basin was the Outer Dock in order to compete with the other docks that were being built within the interior of Rotherhithe. The canal was never a commercial success, being used mainly to carry the produce of the market gardens rather than more lucrative cargoes that its builders had foreseen, so expanding its margins to incorporate docks was a good way of generating additional income. The canal's Rotherhithe section became an integral part of the

network of docks that were constructed throughout the interior of

Rotherhithe. The docks changed the face of Rotherhithe forever, expanding London's ability to handle maritime commerce,

attracting many more workers to the area and leading to the construction

of a lot more housing.

By the late 19th Century Rotherhithe continued to be an important centre of ship

building, for the construction of lighters, sailing barges, naval ships, fabulous tea

clippers and even steam ships. Prestigious ship builders and ship owners lived here, as well as wealthy ships captains and officers of the Honourable East India Company, but the ever increasing influx of dock workers meant that considerable new building was required, and many new blocks of terraced housing grew up along the river to house dockers and their families.