Up until 1851 the main source of lighting and other domestic fuel in the area was Daniel Bennett and Sons Oil Works, which had provided whale oil for the Rotherhithe area. According to Stuart Rankin their presence may account for the late arrival of gas in the area. Daniel Bennett and Son were located on the western side of Rotherhithe, adjacent to the Surrey Basin (now Surrey Water, by the Old Salt Quay pub and the red bascule bridge) and as well as investing in the whaling trade were involved in the South Seas trade, transporting convicts. Daniel Bennett died in 1826 and son William in 1844. The subsequent gasworks were built over their premises.

|

Drawing the retorts at the Great Gas Establishment Brick Lane,

from The Monthly Magazine (1821). Sourced from Wikipedia |

The earliest gas was manufactured, unlike today's natural gas. The supply of gas was a major innovation in the early 19th Century. It was the energy that

eventually supplied first for street lighting, industrial and eventually for domestic applications. In 1792 William Murdoch had supplied his own home with light using gas, and went on to work with engineer William Clegg to develop commercial applications. The Birmingham steam engine manufacturers Boulton and Watt, for whom he worked, started to build small gas works for factories using Murdoch's designs. At the same time, in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries Philippe Lebon displayed his own gas experiments in Paris, influencing German Frederick Albert Winsor who established the Gas Light and Coke Company. The company was granted a Royal Charter in England in 1812 and supplied lighting to the streets of Westminster in 1813, from where it was eventually run out to most of Britain and then Europe and the United States.

|

The last remaining Rotherhithe gasometer as it is today,

built in 1935 |

The earliest application of gas was for street lighting followed by factories and mills. It was rolled out to profitable private enterprises and homes of the wealthy, before finally finding into ordinary households in the late Nineteenth Century, by which time electricity was becoming established. Gas for cooking, and the appliances that made it possible, was available from the mid 19th century for the homes of the wealthy. Homes were only heated by gas from the early 1900s. Showrooms for light fittings, cookers and heating systems were soon set up on high streets. At the same time, gas engines supplied electricity for factories and public and tramway supplies. Although many other private and municipal companies were established,

Winsor's company remained the main private supplier of gas until

nationalization in 1948.

As I have mentioned above, the gas used before the discovery of Natural Gas in the North Sea was manufactured. Manufactured gas was produced by setting fire to combustible materials to produce carbon monoxide, hydrogen and carbon dioxide. As Winsor's company name indicates,coal was the preferred material, and this was "gasified" by heating coal in enclosed ovens which had low levels of oxygen. The gas was then burned to produce light and heat. This required the supply of large quantities of coal, transported in from the country's coal mines, and was a manual process involving men stoking the coal in the ovens at dedicated gasworks.

|

| Making gas from coal. From the National Gas Museum website. |

The initial process in the production of gas took place in the "retorts," where the coal was heated in the oxygen-deprived atmosphere. Every gasworks had a retort house. The Rotherhithe retorts are clearly marked on the 1868 map below. The production and supply of gas was a complicated process that required a considerable amount of technology that was housed in other gaswork buildings. The most obvious visible signal of a gasworks was the gasometer or gas holder. This innovation was designed to solve the problem of patterns in the use of gas, which was used mainly during mornings and evenings, when lighting was most required. To prevent wastage and to regulate supply, gas was stored in gas holders, which stored the gas overnight. Various different designs evolved, and the gas tower is now a familiar part of the urban landscape. Chimneys were also a noticeable feature, used for disposing of unwanted components of the gas production process, and responsible for the introduction of several toxins into the atmosphere. None of the Rotherhithe chimneys survive, but some of them are visible in the 1937 photograph below. To see more about the complexities of gas production see the

excellent Wikipedia page on the subject.

|

Lighting in the Thames

Tunnel, Rotherhithe, 1843 |

Gas first found its way into Rotherhithe in response to a commercial need. When the Thames Tunnel opened in Rotherhithe in 1843, illuminated by 100 gas jets, the gas was supplied by the Phoenix Gas Company. The Phoenix Gas Company had gasworks at Deptford Creek and Bankside and pumped the necessary gas into the area. The Phoenix Gas Light and Coke Company was established by Act of

Parliament in 1824, and purchased the gasworks at Bankside in

Southwark, from the South London Gas Company in the same year. The Phoenix Gas Works was a very successful company, financed by subscription. The Early London Gas Industry

website describes it as follows:

In its company history ‘A Century of Gas Lighting' the South Metropolitan Gas Company described the original Phoenix Company as having ‘a philanthropic, if not a Whiggish, tinge’ - and this is certainly true. The original Phoenix subscribers list, given below, includes many of the great and good of the era - Whigs, Quakers, Anti-Slavers - together with a strong element of local Southwark business men, and many of them would fit into several of these categories. It is a deeply impressive list - it is also, in contrast to some others, a list, which contains some highly principled politicians. There are also a number who can be identified as family and connections of the prison reformer, Elizabeth Fry. Even Derek Matthews in ‘Rogues, Speculators and Competing Monopolies’ was unable to find evidence of corruption - except in the dishonesty of a company secretary in the early 1830s.

The Rotherhithe Gasworks was established in 1851 following the foundation of the Surrey Consumers Gas Company (also known as the Surrey Consumers Gas Association) in 1849, opening in 1855 in competition with Phoenix, occupying the land that had formerly housed the Daniel Bennett and Sons Oil Works. The small company already owned a small gasworks in Deptford, and with the establishment of the Rotherhithe site were able to supply the Rotherhithe peninsula, extend into Bermondsey and eventually parts of Southwark. At the time of construction a wharf was built to accompany the gasworks, and an iron bridge was built to transport coal across Rotherhithe Street to the gasworks beyond, in barrows. The coal was shipped in from the northeast, where it was mined. The gasometers were established at that time. Numbers 1 and 2 had a capacity of 1,600,000 cubic feet between them. There were three by 1868.

In 1879 the South Metropolitan Gas Company took over the site, with its three gasometers. The South Metropolitan Gas Company was founded in 1829 and incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1842 and their gasworks were established on the Grand Surrey Canal on the eastern side of Old Kent Road, enabling them to receive coal delivered from ships to Rotherhithe wharves, via barges on the canal. By 1856 they had seven gasholders on the site. In 1879, the South Metropolitan Gas Company merged with the Surrey Consumers Gas Works and later in the same year Phoenix Gas Company and the South Metropolitan Gas Company were also amalgamated. These mergers gave the South Metropolitan Gas Company the gasworks at Rotherhithe, Vauxhall, Bankside and Greenwich.

|

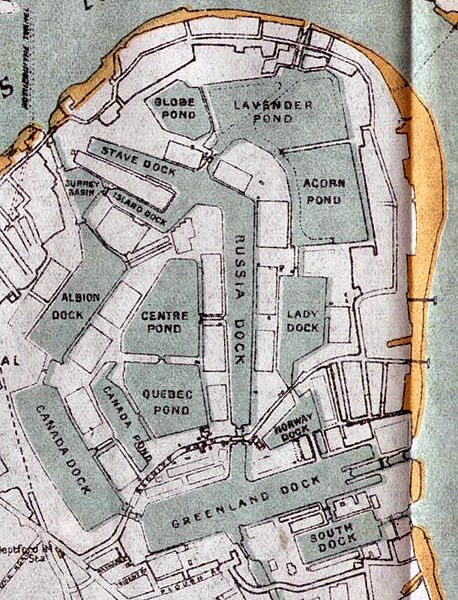

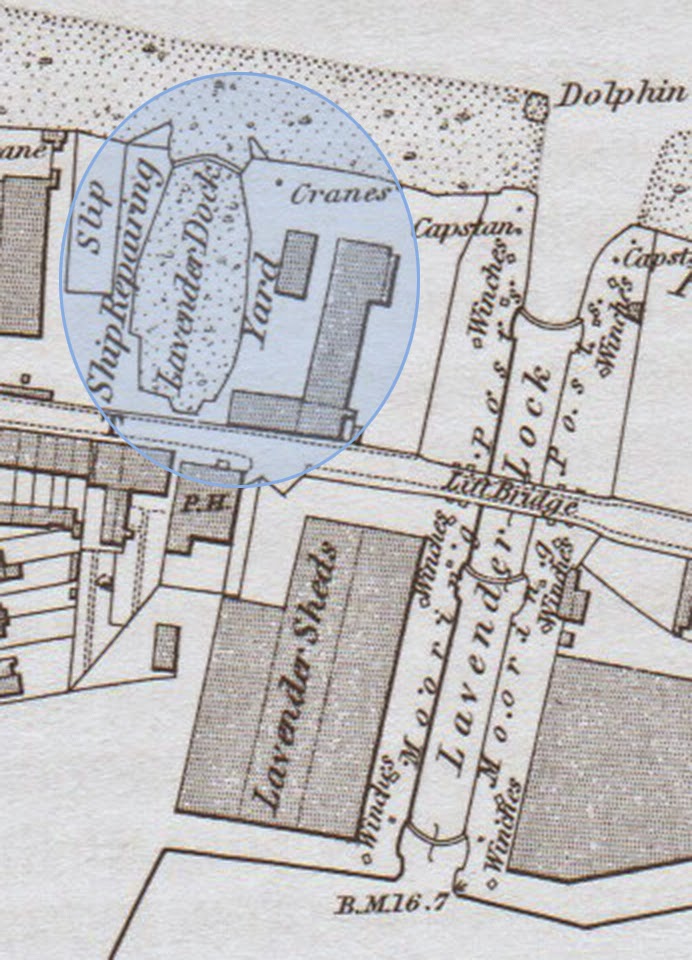

Maps showing the same site in 1868 and 1894. The major difference

between the two maps is the extension of the jetty and the establishment

(shown in dark lines) of the single track railway on the jetty to run

between thejetty and the gaswork site, via the bridge over Rotherhithe.

Click to see the maps properly.

|

|

Women Working in a Gas Retort House during the

First World War: South Metropolitan

Gas Company, London. 1918,

by Anna Airy. Imperial War Museum |

The Rotherhithe site was extended to six and a half acres and the company acquired three riverside properties to improve efficiencies; F.Powell's sea-biscuit bakery at King's Mill Wharf, Mangle Wharf granary, which was owned by Timothy and Company, and Clarence Wharf, then in the hands of S.Cooper. The South Metropolitan Gas Company immediately replaced the existing waterside infrastructure with a new iron jetty in 1882/1883, which received sufficient coal to supply both the Rotherhithe Gasworks and the South Metropolitan Gas Works on the Old Kent Road, to which it was delivered via lighters (un-powered boats) along the Grand Surrey Canal. The bridge over Rotherhithe Street was still furnished with the single track railway. The three gasometers were still there in 1894, by which time the gas

jetty had been expanded and a single track railway put in place to

connect the jetty and the gasworks, the coal supplied by sea on collier

ships from the north-east. The jetty was again expanded in 1908.

During the First World War many men went to war, and much of their work was taken over by women, in a situation that presaged the factory work carried out by women in the Second World War.

In his book The Story of Rotherhithe, Stephen Humphrey describes how the

South Metropolitan Gas Company "was one of the most enlightened

industrial employers in south London." Housing built for their employees included seven houses in Brunel Road in 1926, which were destroyed by bombs during the Second World War. Another housing development was erected in 1931 in Moodkee Street, which consisted of 30 flats in three buildings - Murdock House, Clegg House and Neptune House. Murdock and Clegg houses were named for the British innovators of gas mentioned above.

|

South Metropolitan Gas Works, 1937, with a collier

moored against the wharf |

In 1932 a 18,000 cubit ft gasometer was built (known as number 4), followed in 1935 by one with a capacity of 800,000 cubit ft (number 3). During the Second World War gasometers Numbers 1 and 2 were destroyed.

After the war the jetty was again expanded, this time extended to 200ft so that it could handle colliers that could each transport coal cargoes of up to 2500 tons. Four cranes were installed at the same time and these could shift up to 75 tons an hour each.

Gas supply was nationalized in 1948. The Rotherhithe gas works closed in 1959.

Today, apart from the one remaining gas tower, used to support a cell transmitter, the entire site of the gasworks has been replaced by residential housing built by Bellway Homes in the late 1990s. The bridge between the jetty and the wharf was still in place, when it was in use for a different purpose, in the 1990s (I've not yet found out what the site was used for after the closure of the gasworks). The wharf, in the form of the grey jetty, is still in place, preserved as a condition of the housing development behind it thanks to local protests at its intended demolition. It is substantially smaller than it was. It was supposed to be made available for public use, as part of the Thames Path, but for reasons that no-one seems to know it remains closed, but is a favourite sunbathing spot for cormorants (or shags - I've never been able to tell the difference).

|

| The gas jetty today |

|

A different view of the 1935 gasometer tower today.

Photograph by Stephen Craven. |

|

Neptune House, built by the South Metropolitan Gas

Company in 1931 for its employees.

Photograph by Chris Lordan. |

I got a major insight when writing this post about a dig I was on when I was an archaeologist working in Chester in the 80s. I was working on a Roman site where the Crown Courts are now located, near the former gasworks, which were long defunct. We had excavated a badly subsided Roman road and were now digging through an earlier Roman drain beneath it, which took us very deep. As we dug down below 6ft, our regulation hard-hats firmly on our heads, we found ourselves paddling in tar. The state we were in! I've never seen so much gunge spread so far and wide. We couldn't dig any lower because as fast was we dug the tar oozed in from the vertical sections in which we were standing. Looking at the diagram above, it is quite clear where it was coming from!

With thanks to Stephen Humphrey's and Stuart Rankin's excellent works for the usual kick-start. For those wanting to investigate further, the National Gas Archive might be a good place to start: http://www.gasarchive.org. The National Gas Museum is located in Leicester and has an excellent website: http://nationalgasmuseum.org.uk.

.jpg)